Knowing and Not Knowing

By Simon Ralli Robinson

Introduction

For this essay, I wanted not just to write about science and philosophy, as I did in my first essay, but also comment on the impact that this has had on my own personal journey. It seems to me that my external world, that which I find around me, is very much reflecting my inner world, my emotional struggles and conflicts. My adult life, from the age of twenty, has been dominated by the fact that I have lived the last nineteen years of my life not knowing if I was or was not a father. At many times this not knowing has been pretty much unbearable.

At Schumacher College I have also struggled, albeit academically, thinking about the birth of an electron, coming into and out of existence, the birth of consciousness, the birth of our universe, and even the birth of the first duality, and as I have read a little deeper, I have seen how perhaps the majority of scientists have struggled with this ambiguity, and this knowing and not knowing too. Was I realising that this facet of life as we know it is fundamental, and if I could come to terms with this ambiguity in the universe, and come to accept it with a certain state of grace, could that help me come to terms and feel a deeper sense of ease and peace, despite my own personal knowing and not knowing too?

Visions of Time and Space

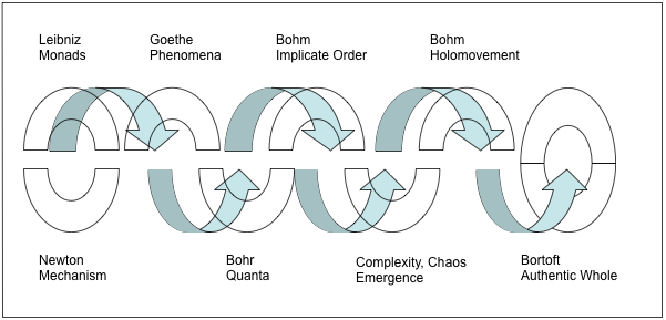

In my previous essay, “The Scientist’s Search for the Soul” I surveyed the development of scientific thinking from the times of Newton and Leibniz to the present day. I modelled my explorations in the form of a wave diagram, as seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: The Wave Model of Scientific Thinking

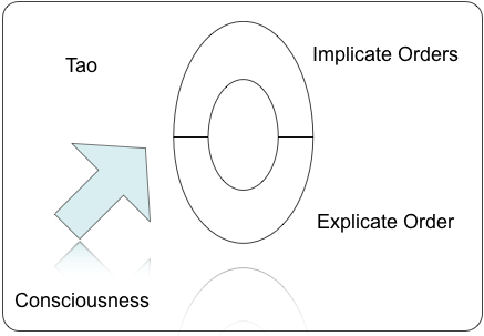

Towards the end of November last year, after I had completed the module on Chaos, Complexity and Gaia Theory, I had a vision. In this vision, I could see how everything was part of an enormous cosmic dance, everything was interconnected, coming into being, existing, and then melting away in a beautiful dynamic array of patterns and colours. This vision appeared to me to be a visual representation and an conscious experience of Bohm’s holomovement. However, within this vision, it was also made clear to me that this was still not the ‘ultimate reality,’ that although the world we live in is one of illusion, so were the higher implicate orders, the higher dimensions of reality. For at one and the same time, I was also shown in this vision the relationship of myself to the Tao, and I was experiencing my own consciousness as it related to the explicate order, the implicate orders and the Tao.

In an instant I grasped what the vision was attempting to teach me. The vision spoke to me and said:

‘Consciousness is the Tao looking back in on itself.’

This made perfect sense to me, and I realised that the final figure in my wave diagram was not the end of the story. For in understanding the holomovement, and the relationship of the parts to the whole, these arise out of a ground, the ground of which I understand as the Tao.

Phillip Frances, our course tutor, drew my attention to a quote from Soren Kierkegaard, which paralleled this vision:

“The human is Spirit. But what is Spirit? Spirit is the Self? But what is the Self? Is the Self a relationship that acts upon its self, or it is the relationship by which the relationship relates itself to its self; the Self is not the relationship but the relationship that relates itself to its self.”

I created the following diagram, Figure 2 below, to explain my vision schematically. It represents a movement in my own thinking beyond just thinking about the whole and the parts, the final section of my wave diagram in Figure 1. In Figure 2, which suffers from being a static image on a page, there is movement between the implicate and explicate orders. But it also attempts to show how these arise from the stillness of the Tao, and that consciousness arises from the Tao to perceive these movements.

Figure 4: Schematic of my vision of the dynamic and the still

Of course the obvious contradiction is that I have labelled some area as Tao, but as the Tao Te Ching makes clear, “Tao called Tao is not Tao.” This phrase has also been translated as “The gateway to all mystery.” My vision did not explain the Tao in any way shape or form, I just had a sense of it being there and a sense of it being the ground from which all arises.

During the final week of “Science Meets Spirit”, I had the opportunity to ask our teacher Ravi Ravindra about my vision, and in particular to comment on the phrase ‘Consciousness is the Tao looking back in on itself.’ I did not mention to him that I had received this definition in a vision, and he began by saying that “Although he had not heard that definition, it sounded rather nice.” He went on to say that when Buddhism went from India to China, the principle of Thurma was translated as the Tao. Thurma would be the foundational principles of the order, the cosmological order, the social order. So one could say that that one feature of the Tao is that it is like the ordering principles of consciousness. Ravi was reflecting on my phrase as opposed to saying it was one thing or another.

I had also asked the same question of Jules Cashford, who had taught us in the previous module, as I wanted to see if this concept of consciousness in relationship to the Tao had any resonance from within a Jungian framework. She answered:

“I know we tend to think of consciousness and unconsciousness within ourselves, but the more Jung goes into the idea, the wider it becomes and actually in the end extends to the whole universe. If it is unconsciousness by definition we can't say where it ends. We are back to the Tao - just speak in negatives in what you know, don't go there. Not this, not that.”

My vision, of simultaneously holding the seemingly contradictory notions of motion and stillness had made a massive impact on me, and it was this vision that inspired my decision to review what would seem to be a very different view of the universe from Julian Barbour, an independent physicist who since 1969 moved his family to a farm in Cambridgeshire where he could contemplate Time, and could question the very existence of time itself.

Quantum Theories of the Dynamic and the Still

In his book, “The End of Time” Barbour notes how in 1963, a single sentence of Paul Dirac’s would transform his life:

“This result has led me to doubt how fundamental the four-dimensional requirement in physics is.”

Dirac was questioning the very fundament concept of twentieth century physics, the space-time continuum. From this, Barbour went on to consider what is time? He concluded that “time is nothing but change.”

Rather than making an assumption that time exists, Barbour seeks to explain how a theory of time emerges from timelessness. He does this by introducing the concept of ‘instants of time’ which are not dependent on some thing that flows forward in time, but which contain their own structure, or as Barbour claims, “possible instantaneous arrangements of all the things in the universe. In themselves, these configurations are purely static and timeless.” He then introduces a special class of instants of time he calls time capsules. He defines time capsules as “any fixed pattern that creates or encodes the appearance of motion, change or history.” It is these time capsules which create the illusion of time. Time capsules do have a cause, but time play no role in that cause. Barbour defines time capsules more formally as “Any static configuration that appears to contain mutually consistent records of processes that took place in a past in accordance with certain laws may be called a time capsule.”

I think this paragraph is one of the most interesting for me:

“The lesson we learned from Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo is here very relevant. They persuaded us, against what seemed to be overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that the Earth moves. They taught us to see motion where none appears. The notion of time capsules may help us to reverse that process - to see perfect stillness as the reality behind the turbulence we experience.”

This is very suggestive to me of the Tao. I sent an email to Barbour asking about the potential for integrating the dynamic theory of Bohm into his theory where movement is an illusion of perception. He replied to me:

“It has exactly the same ontology, and in this respect is close. However, it is static and has been perceptively called 'Bohm without the trajectories'. You will probably be familiar with the concepts of primary and secondary qualities, which were first clearly defined by Galileo. He took shape, position and motion to be primary qualities and colours, tastes etc to be secondary qualities 'excited' in the mind by the primary qualities. I provisionally make a similar division, but put motion among the secondary qualities. Bohm was especially keen to have motion as a primary quality. His interpretation of quantum mechanics was formulated well before the Wheeler-DeWitt equation and the associated problem of time was discovered. I do not know if he ever learned about it. He certainly lived long enough.”

Dialogues Between Scientists and Spiritual Leaders

Although Bohm’s theory of the implicate order and wholeness does in one respect appear to be dynamic, in contradiction to Barbour’s, it was instructive to me to read the dialogues between Bohm and Krishnamurti, in the very similarly titled book “The Ending of Time.” I was left with the feeling that ultimately Bohm and Krishnamurti did not finish with a total understanding and agreement with one another, but many parts of the conversations are very illuminating with the issues they are exploring.

DB: Let’s try to put it that thought, as we have generally known it, is in time.

K: Thought as we know it now is of time.

DB: It is based on the notion of time.

K: Yes, all right. But to me, thought itself is time.

DB: Thought itself creates time, right.

K: Does it mean, when there is no time there is no thought?

Bohm continues in a later dialogue to note that “implicitly, time is taken as the ground of everything in scientific work.” Much of the discussions are centered around the notion of ‘the ground.’ Krishnamurti explains that in order to experience the ground, the human being has to remove all trace of ego:

“The ground has certain demands: which are, there must be absolute silence, absolute emptiness, which means no sense of egotism in any form, right? Would you tell me that? Am I willing to let go all my egotism, because I want to prove it, I want to show it, I want to find out if what you are saying is actually true? So am I willing to say, “Look, complete the eradication of the self?”’

The reason I draw attention to this aspect of the dialogues is that although these are two individuals with such a deep insight into their own fields of experience and expertise, it does resonate with the vision I had of the Tao. In my vision I felt that one could only really realise the Tao when one had truly removed all concepts of self and reality, i.e. the soul had fully merged back into the ground from where it came.

A second reason I wished to refer to these dialogues was to draw attention to the last few years of David Bohm’s life. These are told in Bohm’s biography by F. David Peat “Infinite Potential.” For within the last few chapters we gain an alternative insight into the deep distress that Bohm sometimes experienced during his relationship with Krishnamurti. Bohm felt that although Krishnamurti had been able to achieve certain insights, these were not the result of a complete lack of conditioning, but of a different kind of conditioning to most other people. Bohm noted how Krishnamurti “does not allow anyone to say “Stop this part of the teaching is not true.” For this would be to challenge the whole of K’s life.”

Bohm became increasingly frail, and also suffered from deep depression. Bohm came to doubt the validity of his lifes work, and this plagued him terribly. Whereas Bohm ended his relationship with Krishnamurti under a cloud, he did find solace in a series of meetings between Western scientists and Native Americans. As Peat recalls:

“As the discussions continued, Bohm learned about the process-based worldview of the Blackfoot, Ojibwa and Micmaq. Everything was said to be in flux, and this constant change is reflected in their verb-based language. At last Bohm had found a people whose metaphysics strongly mirrored his own.”

Whereas Bohm felt that Krishnamurti was wrong to assert that everything he (Krishnamurti) said was the truth, over the last twenty years or so there have been a very different set of on-going dialogues between The Dalai Lama and western scientists from very diverse disciplines. In his book “The Universe in a Single Atom” The Dalai Lama makes two interesting observations:

“One of the most important philosophical insights in Buddhism comes from what is known as the theory of emptiness. At its heart is the deep recognition that there is a fundamental disparity between the way we perceive the world, including our own existence in it, and the way things actually are.”

And

“To a Mahayana Buddhist exposed to Nagarjuna’s thought, there is an unmistakable resonance between the notion of emptiness and the new physics. If on the quantum level, matter is revealed to be less solid and definable than it appears, then it seems to me that science is coming closer to the Buddhist contemplative insights of emptiness and interdependence.”

The Dalai Lama will often meet a small group of scientists for an entire week, with the explicit instruction that there is to be no area of investigation and enquiry that is off-limits. These discussions when one reads them show an obvious profound impact on all the attendees. Two examples of these dialogues are to be found in “Sleeping, Dreaming and Dying,” i.e. pivotal moments in consciousness, and in “The New Physics and Cosmology” where the discussions are based around Buddhism and theories of relativity, quantum physics and cosmology.

In “Sleeping, Dreaming and Dying” The Dalai Lama over the course of a few pages provides one of the clearest outlines of Buddhist conceptions of mind, body and consciousness.

“Does brain function act as substantial cause for mental processes, or does it provide cooperative conditions? The substantial cause would be identified as the very subtle mind, or primordial mind. But I understand the heart of your question to be: what is it that provides the connection between the very subtle mind and the gross body or the gross mind? Here we speak of the very subtle energy-bearing five coloured radiance......It’s not true that you have two distinct continua of consciousness, one very subtle, the other gross. Rather gross consciousness stems from the very subtle mind. It’s something separate.”

Later in “The Universe in a Single Atom” The Dalai Lama makes the point that he does not think that neuroscience has any real explanation of consciousness itself. That mind is an emergent property of a brain made from matter is a metaphysical assumption. Francis Crick and Christof Koch in a key paper “Consciousness and Neuroscience” also outline just how much we still do not know about the neural correlates of consciousness, but are adamant that not only that these will be found, but that an entire explanation of consciousness and qualia of consciousness will be fully explainable at the neural level. One complementary way forward, as advocated by Francisco Varela, is that incorporated into the study of consciousness should be “a fully developed and rigorous methodology of first person empiricism.” Many of these are captured in the collection of essays “The View From Within - First Person Approaches to the Study of Consciousness” edited by Varela and Shear.

Of Atoms and Archetypes, Dreams and Visions

On our course “Science Meets Spirit” both Ravi Ravindra and Arthur Zajonc both talked about the benefits of combining a rigorous scientific approach to the study of nature with inner disciplined meditation. This is to ensure that the scientist does not stay blinkered to the deep insights gained from the deepest meditative states that it is possible to achieve. These may take at least ten years or more of practice to achieve. But whereas these are within the conscious control of the practitioner, another form of insight, that of dreams and visions, have clearly provided a huge amount of insight to the world’s greatest scientists, and it is these that I now wish to explore.

A recent article in The Independent, looking at the truth behind the story of how a falling apple inspired Newton’s laws of gravity, revealed the background to the discovery of the chemical transmissions of nerve cells:

“Otto Loewi, the German physiologist, spent 17 years trying to come up with definitive proof that nerve impulses were transmitted chemically, and was finally struck by inspiration one night when he had a dream showing him how to carry out a key experiment using a frog's heart. He immediately went to his laboratory to conduct the experiment, noting that electrical stimulation of a frog's vagus nerve released a chemical, now known to be the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which controlled the heart rate.”

Alan Rees, writing in The Mail on Sunday, also revealed the following astonishing story, which he subsequently confirmed with Crick in person:

“Dick Kemp told me he met Francis Crick at Cambridge. Crick had told him that some Cambridge academics used LSD in tiny amounts as a thinking tool, to liberate them from preconceptions and let their genius wander freely to new ideas. Crick told him he had perceived the double-helix shape while on LSD.”

These moments of insight still remain a mystery to science, in that we still can not explain where they come from. Many scientific discoveries do not come from logical step by step deductions, from a researcher who remains objectively apart from that which he or she is analyzing.

Figure 3: Pauli’s World Clock

One of the most remarkable stories from science I feel is that of Wolfgang Pauli, a world-renowned physicist who in 1945 won the Nobel Prize. With a personal life that was breaking down, and frequently resorting to alcohol, he turned to Carl Jung for help. Their friendship resulted in many letters between these two thinkers, and their correspondence between 1932 and 1958 are published in the book “Atom and Archetype” by C.A. Maier. In both these letters and many personal meetings, Pauli would document and discuss in great detail his dreams with Jung. One of the most striking dreams, that left a profound impact on Pauli was of his world clock, illustrated by W. Byers-Brown in Figure 3 above.

As F. David Peat notes in his description of Pauli’s World Clock, Jung saw the image as a mandala of ‘the self’ and also noted much that reflected symbolism from both alchemy and the Qabala. But Peat also suggests that since Pauli was also at the time interested in looking deeper into the mysteries of elementary particles and their abstract symmetries, the image is capable of many levels of interpretation.

In a letter to Jung, in 1940, Pauli spoke of how he had continued to work on his interpretation of his dream of the world clock, and in thinking about the concept of time had been influenced by the I Ching and the commentary of Richard Wilhelm on the I Ching.

“The motif of the projection of various periodic processes onto each other, as a sort of associative connection, seems to play an important role here, especially as, psychologically speaking, the concept of time is based on memory, powers of recall, and association.”

Interestingly, Jung explains to Pauli that he is worried that he is not able to comprehend mathematical or physical thinking in detail, protesting that it is “As though I am groping my way through dense fog.” Jung had described his own concepts from physics as ‘dreamlike’ and worried that they were not concrete. Pauli wrote to assure Jung that not all scientists were gifted mathematicians:

I know a lot of people (such as chemists and radiologists) who approach physics from the experimental angle, and they assure me that they have to imagine the physical conceptions ‘graphically’ since the mathematical-formula apparatus is not accessible to them. With none of them would I speak of the ‘dreamlikeness’ of their concepts but would call their concepts ‘concretist.

Closing Thoughts

I recently watched two BBC documentaries, one on Complexity Theory and Chaos and the other by David Attenborough celebrating the 150th anniversary of the publication of Darwin’s theory of evolution. In both cases, there was an assumption that between them, these two areas solved all questions regarding the emergence and evolution of life, and that there were no mysteries to be solved. But as we have seen, in quantum physics, the same experimental observations can lead to two opposite conceptions of the universe, one where all is dynamic and one where all is still. Neither of the authors of these two theories claimed to have the definitive answer, with Bohm still searching for the ultimate ground, and Barbour not managing to successfully incorporate consciousness into his framework.

Although for me the explorations of the relationship between physics and psyche of Pauli and Jung were too human-centric, they also suggest that perhaps the material world does have a subjective element, and that the psychic world could have a more concrete aspect than has previously been realised. Indeed, by developing the concept of synchronicity, where personal psychological meaning is derived from physical events, can we move away from a material reductionist concept of causation, to one of pattern and flow?

I wanted to explore how scientists utilised visions and dreams to inspire and inform their thinking, and to see how they were able to resolve the many contradictions and paradoxes within science. Some still strive for a unified theory of everything, whereas others enjoy the great mystery, and honour the ground from which they may never reach through knowledge alone. My definition of consciousness as ‘The Tao looking back on itself’ captures the issues many philosophers have come across in terms of analysing that which references itself.

Andy Lloyd and Simon Ralli Robinson

My own vision related at the start of this essay came from a vision I had during an ayahuasca ceremony. It is ayahuasca and the extraordinary expansion of consciousness and understandings gained from it that I will be writing about for my dissertation. I do have a few photos of my daughter, and when I look at her, sometimes she is like a particle, and sometimes she is like a wave. Sometimes I see myself in her, and sometimes I do not see the family resemblance that others see. In another ayahuasca ceremony the insight came that ultimately it does not matter if she is or is not my daughter, for ultimately we are all as one at the deepest level of reality. If within my own personal transformations as a result of both taking on an MSc in Holistic Science, and the transformations experienced with ayahuasca lead to resolution, that will be enough for me and as the Tao suggests, life is to be lived enjoying the great mystery.

By Simon Ralli Robinson, March 2010

Author of "The Yogi Footballer"

References

Barbour, J. (2000) The End of Time Phoenix

Krishnamurti, J. and Bohm, D. (1985) The Ending of Time Harper Collins

Kierkegaard, S (1849) The Sickness Unto Death

Lao-Tzu (1993) Tao Te Ching - Translated by Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo Hackett, Indiana

Meier, C.A. (2001) Atom and Archetype Princeton

Peat, F.D (1987) Synchronicity Bantam

Peat, F.D. (1997) Infinite Potential The Life and Times of David Bohm Addison Wesley

The Dalai Lama (2005) The Universe in a Single Atom Abacus

The Dalai Lama (1997) Sleeping, Dreaming and Dying Wisdom

Varela, F. Shear, J. (1999) The View from Within First Person Approaches to the Study of Consciousness Imprint Academic

Zajonc, A. (2004) The New Physics and Cosmology - Dialogues with the Dalai Lama Oxford University Press

Newspaper Articles

"Nobel Prize genius Crick was high on LSD when he discovered the secret of life” Alun Rees, Mail on Sunday, 8th August 2004

“The core of truth behind Sir Isaac Newton's apple” Steve Connor, Independent, 18th January 2010

Images

Image of Pauli’s World Clock (Figure 3) from www.arthurimiller.com